The differences between Chinese and Western thinking patterns have long been a subject of academic and cultural exploration, rooted in distinct historical, philosophical, and social contexts. These differences influence how individuals perceive the world, communicate, solve problems, and interact with others. Understanding these distinctions is not only crucial for cross-cultural communication but also for fostering global collaboration in an interconnected world.

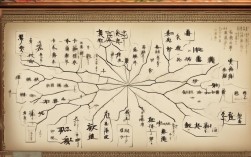

At the core of Chinese thinking lies holism (整体性思维), which emphasizes interconnectedness and the prioritization of the collective over the individual. This perspective is deeply influenced by Confucianism, Taoism, and traditional Chinese medicine, all of which view the universe as an integrated system where elements are interdependent. For example, in decision-making, Chinese people often consider the impact on family, society, or the group, rather than focusing solely on personal interests. In contrast, Western thinking tends to be analytical (分析性思维), breaking down complex problems into smaller, manageable parts. This approach, shaped by Greek philosophy, the Enlightenment, and the Scientific Revolution, values logic, objectivity, and individualism. Westerners typically prioritize personal goals, explicit rules, and direct solutions, often viewing issues in isolation rather than as part of a larger whole.

Another key distinction is in communication styles. Chinese communication is often high-context (高语境文化), relying on implicit messages, nonverbal cues, and shared cultural understanding. For instance, a Chinese speaker might say, "It’s a bit cold in here" to indirectly suggest closing a window, expecting the listener to infer the intended meaning. Harmony (和谐) is highly valued, so direct confrontation or disagreement is typically avoided to maintain social cohesion. In contrast, Western communication is usually low-context (低语境文化), characterized by directness, clarity, and explicit verbal expression. Westerners tend to "say what they mean and mean what they say," prioritizing transparency over ambiguity. A Westerner might directly state, "Could you please close the window?" to avoid misunderstanding. This difference can lead to miscommunication: Chinese may perceive Westerners as blunt or rude, while Westerners may find Chinese communication vague or evasive.

The approach to time also reflects divergent thinking patterns. Chinese culture tends to be polychronic (多时间导向), flexible, and cyclical. Time is seen as fluid, with multiple tasks often handled simultaneously, and long-term relationships are prioritized over strict schedules. For example, a business meeting in China might start later than planned or extend to accommodate personal connections, as building trust is considered more important than punctuality. Western cultures, particularly in North America and Northern Europe, are monochronic (单时间导向), viewing time as linear, finite, and something to be managed efficiently. Punctuality is highly valued, tasks are completed sequentially, and schedules are strictly followed. A Western businessperson might view a delayed meeting as disrespectful, while a Chinese counterpart may see it as a sign of relationship-building.

In terms of problem-solving, Chinese thinking often emphasizes synthesis (综合) and adaptation. Rather than seeking a single "correct" solution, Chinese people may consider multiple perspectives and aim for a compromise that satisfies all parties. This approach is evident in traditional Chinese medicine, which balances the body’s "yin" and "yang" rather than targeting isolated symptoms. Western problem-solving, by contrast, tends to be linear and reductionist (线性和还原论), focusing on identifying the root cause of a problem and applying a standardized solution. Scientific methodology, with its emphasis on hypothesis-testing and empirical evidence, exemplifies this approach. For example, a Western doctor might prescribe a specific medication for a diagnosed illness, while a traditional Chinese practitioner might recommend a combination of herbs, diet, and lifestyle adjustments to restore overall balance.

Educational philosophies further highlight these differences. Chinese education is often rote-based and teacher-centered (死记硬背和以教师为中心), with a strong emphasis on memorization, discipline, and respect for authority. Students are expected to absorb knowledge from textbooks and teachers, and success is measured by academic performance and exam results. This approach reflects the Confucian value of education as a means to self-cultivation and social order. Western education, particularly in progressive societies, tends to be student-centered and inquiry-based (以学生为中心和探究式学习), encouraging critical thinking, creativity, and independent exploration. Classrooms often promote debate, questioning, and hands-on learning, with an emphasis on developing individual strengths and passions.

These thinking patterns also extend to business and management. In Chinese organizations, hierarchy and collective decision-making are prominent. Leaders are expected to be paternalistic, guiding and supporting their subordinates while maintaining authority. Consensus is often sought to ensure group harmony, and long-term relationships (guanxi, 关系) play a critical role in business success. Western businesses, however, tend to be flatter and more individualistic (更扁平化和个人化), with decision-making often delegated to those with expertise. Performance is evaluated based on individual achievements, and competition is encouraged to drive innovation.

| Aspect | Chinese Thinking | Western Thinking |

|---|---|---|

| Core Focus | Holism, interconnectedness, collective harmony | Analysis, individualism, logical reasoning |

| Communication | High-context, indirect, relationship-oriented | Low-context, direct, task-oriented |

| Time Perception | Polychronic, flexible, cyclical | Monochronic, linear, schedule-driven |

| Problem-Solving | Synthesis, adaptation, compromise | Linear, reductionist, root-cause focused |

| Education | Rote-based, teacher-centered, discipline-focused | Inquiry-based, student-centered, creativity-focused |

| Business Culture | Hierarchy, consensus, guanxi (relationships) | Flatter structure, individual performance, innovation |

Despite these differences, it is important to avoid overgeneralization. Globalization and cultural exchange have led to increasing blending of these thinking patterns. Many Chinese individuals and organizations now adopt Western analytical approaches in fields like technology and finance, while Westerners are increasingly recognizing the value of holistic and relationship-centered thinking in areas such as sustainability and leadership. The key to cross-cultural success lies in cultural intelligence—the ability to understand, adapt to, and appreciate diverse perspectives.

FAQs

Q1: How do Chinese and Western thinking styles affect teamwork in international projects?

A1: Chinese teams often prioritize group harmony and consensus, spending time building relationships before making decisions. This can lead to slower initial progress but stronger long-term collaboration. Western teams, favoring efficiency and directness, may move quickly to task allocation and problem-solving. Potential conflicts arise when Western teams perceive Chinese decision-making as indecisive, while Chinese teams may view Western approaches as impersonal or overly aggressive. Successful international teams bridge this gap by encouraging open communication, establishing clear roles, and respecting each other’s cultural norms.

Q2: Can Chinese thinking patterns be applied to Western contexts, such as business or education?

A2: Yes, many elements of Chinese thinking are increasingly valued in Western contexts. For example, the holistic approach to problem-solving is useful in addressing complex global issues like climate change, where interconnected systems require integrated solutions. In education, Chinese emphasis on discipline and foundational knowledge complements Western focus on creativity, leading to more balanced learning outcomes. In business, Chinese relationship-building (guanxi) can enhance trust and long-term partnerships, particularly in industries like manufacturing or international trade. However, adaptation is key—blindly applying Chinese practices without considering Western cultural values may lead to resistance or inefficiency.